The following is an edited transcript of my talk “All the World’s a Screen: How Improv and Playwriting Can Inform Digital Narrative” given at Narrascope 2019.

Overture

Before we get into the talk proper, I wanted to start with a word of caution that I heard from Jack Viertel, a Broadway producer and creative director for over 160 shows: “The minute the curtain goes up on a show, the audience is in trouble.”

Even though this isn’t a show exactly, these seats look kind of like an audience, so I wanted to make sure that no one feels like they are in trouble before the talk.

The trouble Viertel refers to here is the realization that happens as the curtain of a show rises: you’ve locked yourself in a room for ninety minutes to three hours with no idea what’s about to happen. That can be very scary. So before I get started, I’d like to try to settle a few of the fears that may be happening in this room.

The first one: you might be wondering if you recognize me, or know who I am, and if you’re not one of my three friends in this room, the answer is that you probably do not. You can stop worrying about that right now. A little about myself to make you feel a little more comfortable: I’m not a game designer during the day, I’m a UX designer. Outside of work though, I’m a playwright and an improviser, with performances across the country on both.

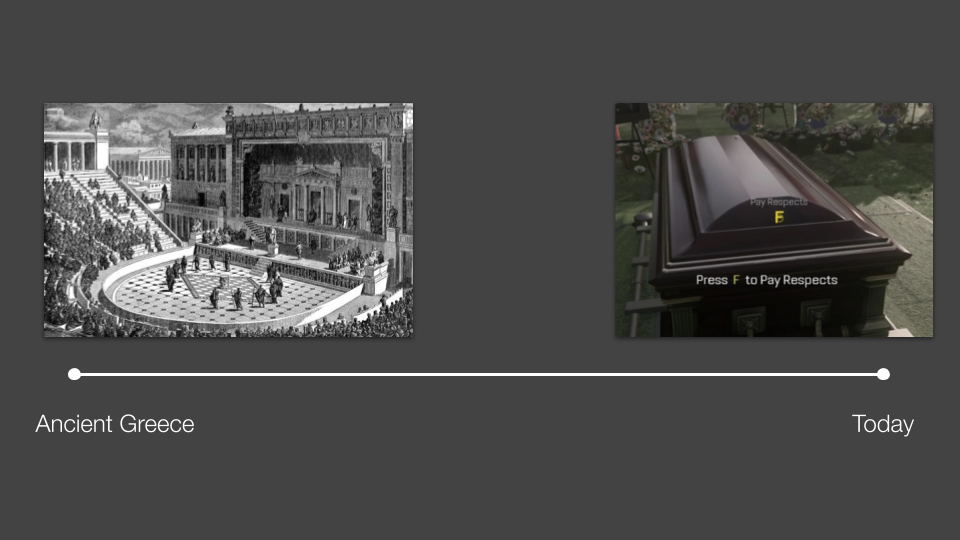

In addition, I also love to read and study the history and theory behind theater, playwriting, and improv. There’s over 2,500 years of theater theory that’s been written, and over half a century of writing on improv. That’s hopefully addressing what your second fear might be: what am I doing speaking at this conference? The answer, as you now know, is that I’m a huge nerd. This theory forms my narrative worldview every time I not only see a play or improv show, but also to play a game. It’s the lens that I channel narrative through (if you ever go to see a movie with me, I’m liable to spend the next week dissecting it through the lens of Aristotle’s Poetics). Because I love to play games, this is the lens through which I experience digital narrative. And I’ve noticed that when you view games through this lens of theater, there’s lots of interesting insights that come out.

My hope for this talk is to essentially to take the entire 2,500 year history of narrative theory from ancient Greece and through today, and show what happens when you look at modern narrative games through that lens. Hopefully that addresses the largest fear: what are we going to spend the next 45 minutes to an hour talking about?

Specifically, I’m hoping to inform about these three topics:

- Answering the question: What are the mechanics that make theater work?

- Convince you that similar mechanics are at play in games and digital narrative

- Share some insights when we view narrative games through this lens.

As a device, I’ve divided this talk up into three acts. So, the curtain rises on…

Act I

I want to start by thinking of the pixel. The pixel is a small atomic unit that any kind of digital graphic, no matter how complex, is built with. From this tiny, little atom, huge, beautiful, inspiring images are built.

There is also a single atomic unit for works of theater: the action. All theater is made up, at the most basic level, of actions. A play is nothing more than a single sequence of actions. David Ball says “A play doesn’t describe action, it doesn’t contain action, a play is action.”

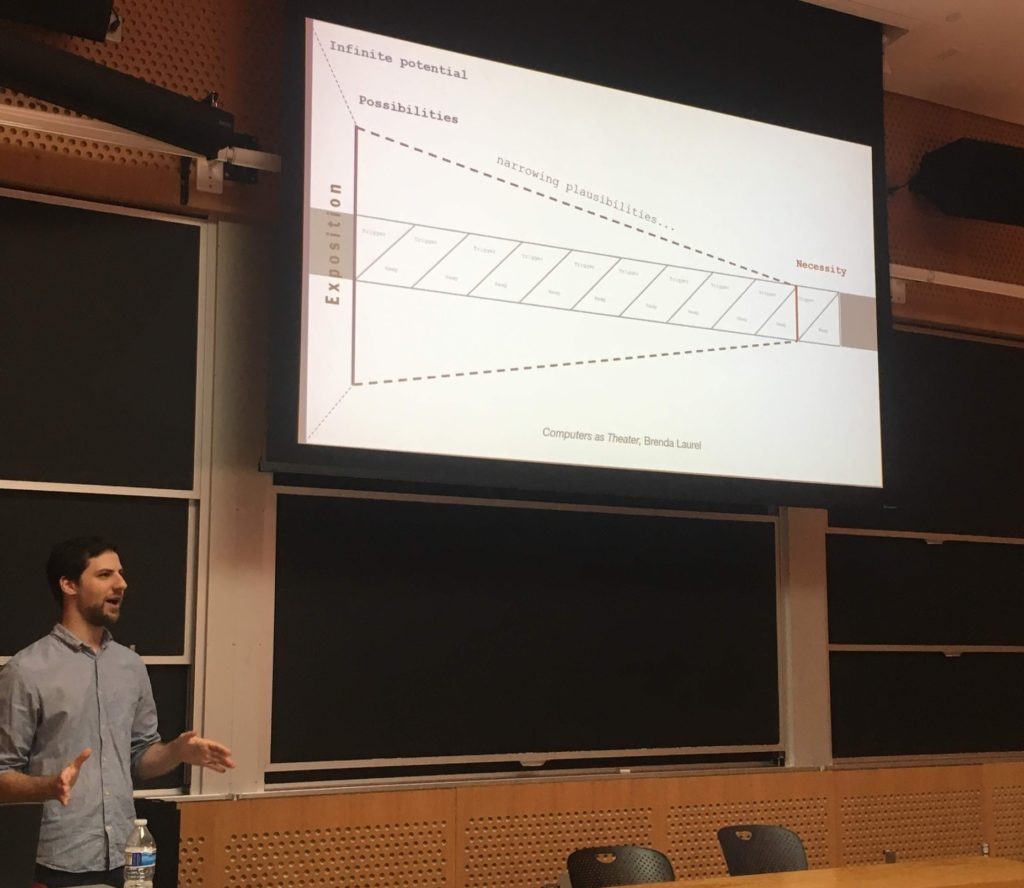

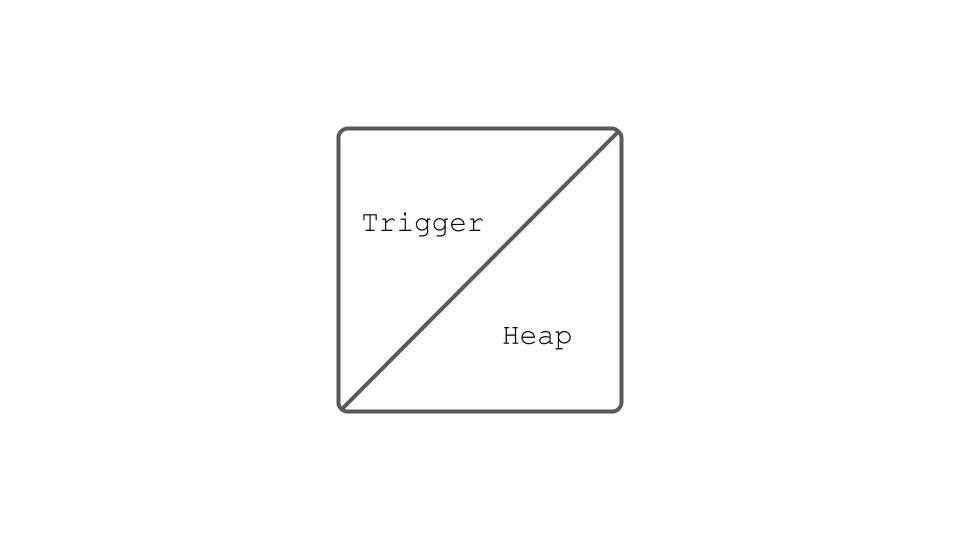

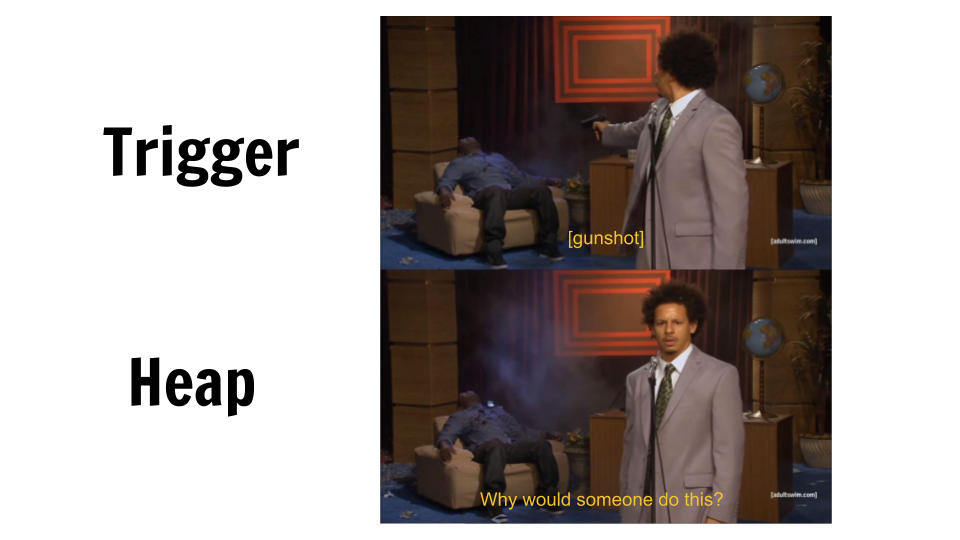

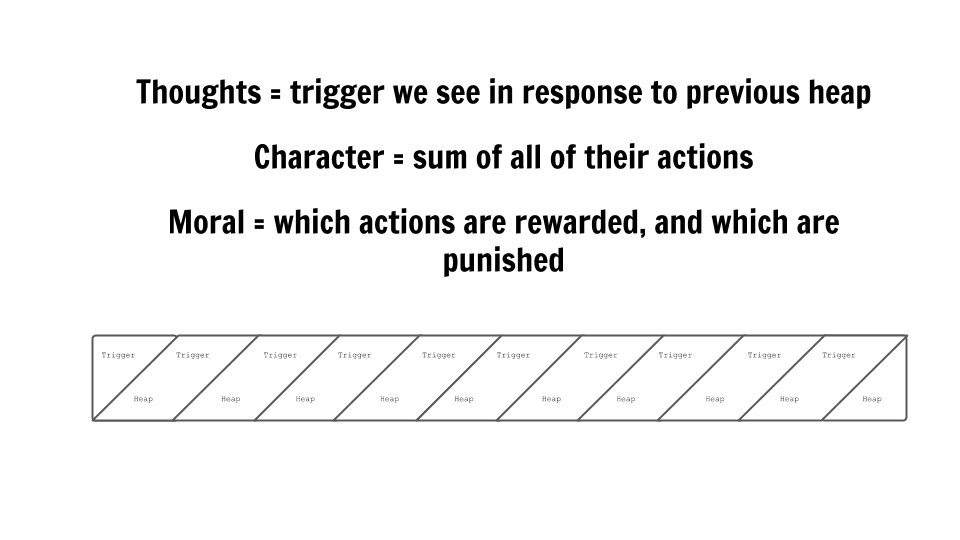

Which leads to the question: what is an action? It isn’t just anything happening on a stage. It’s actually two parts: a trigger, and a heap. Or a cause, and an effect. I pull the trigger (cause), someone falls into a heap (effect). Something that happens, but doesn’t cause anything else to occur as a result, wouldn’t be an action. Action requires both halves.

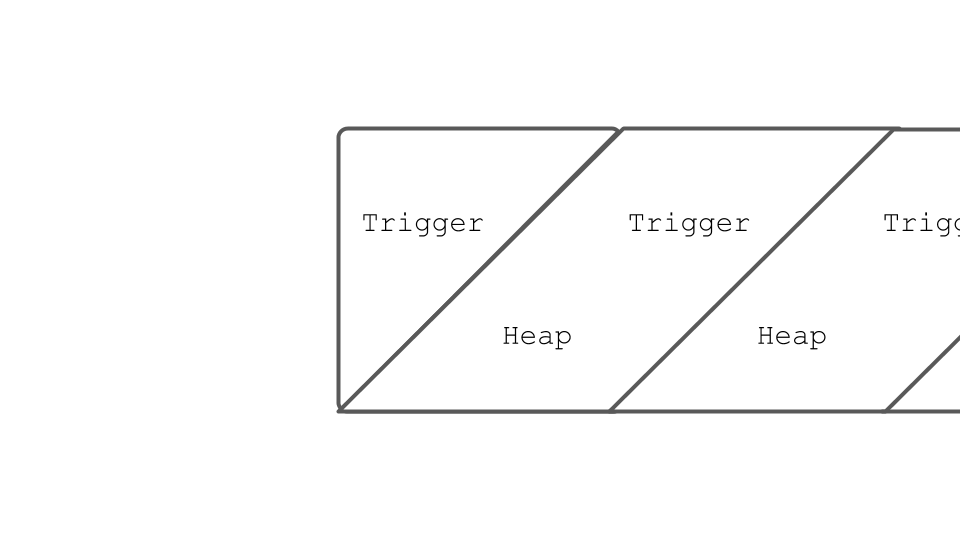

That’s important because the sequence of actions that make up a play (trigger-heap, trigger-heap, etc.) are intimately connected, where the heap of one trigger becomes the trigger for the following heap. They’re connected one after another, for the entirety of the play.

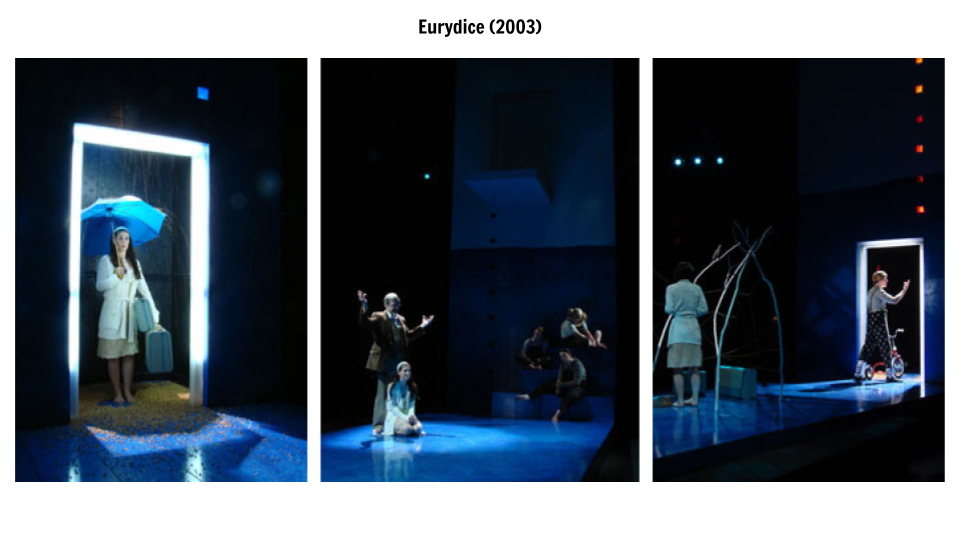

A great example of this is the play Eurydice by Sarah Ruhl. It’s based on the classic myth of Orpheus and Eurydice, but it takes the final action of the story (Orpheus looks back at Eurydice while leading her from the underworld), and asks the question: what could the trigger have been that caused that action? And what would have caused that trigger? Backwards and backwards, and explores this from Eurydice’s perspective.

It tells the story of her love for Orpheus, so that in this telling, when he’s leading Eurydice back, she calls out to him, causing him to turn around. Eurydice calls (trigger), and Orpheus looks back (heap). It flips the story by inserting that trigger, forcing the viewer to reinterpret the nature of the final action.

So a play is not just a sequence of actions in a row, but a sequence of connected triggers followed by heaps, until a the show is finished.

Let’s talk about games.

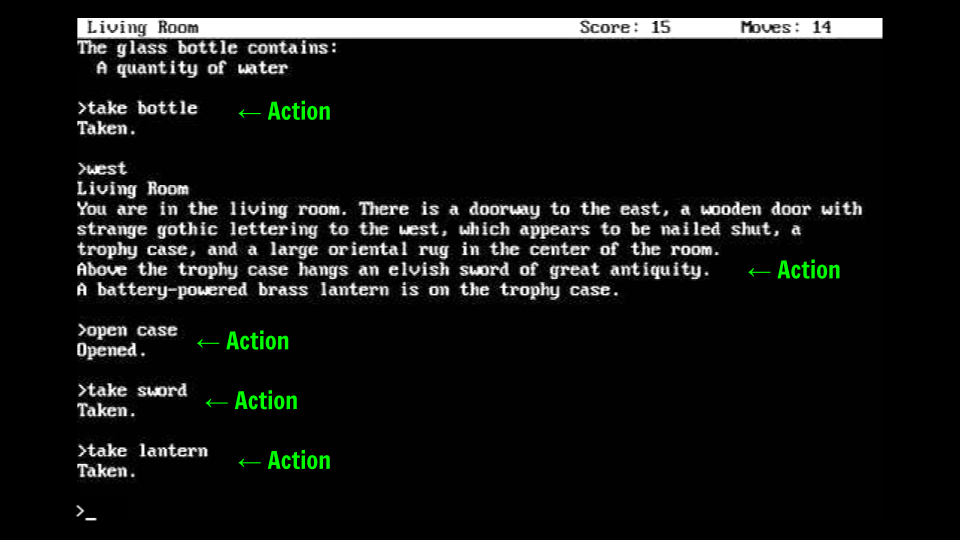

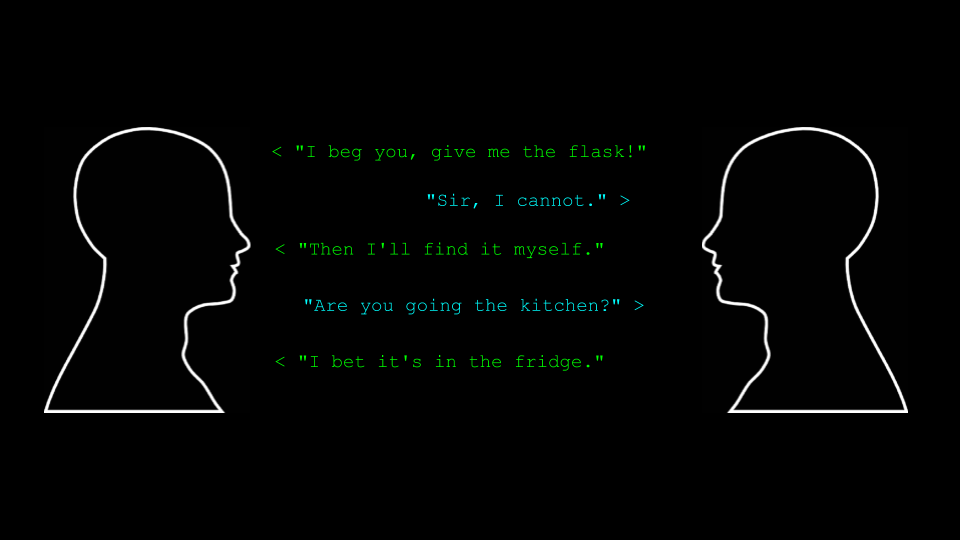

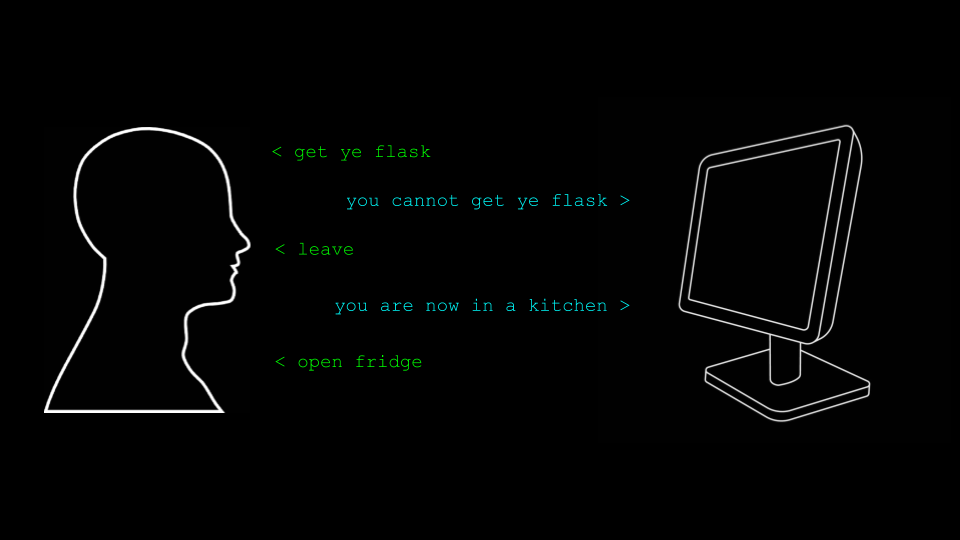

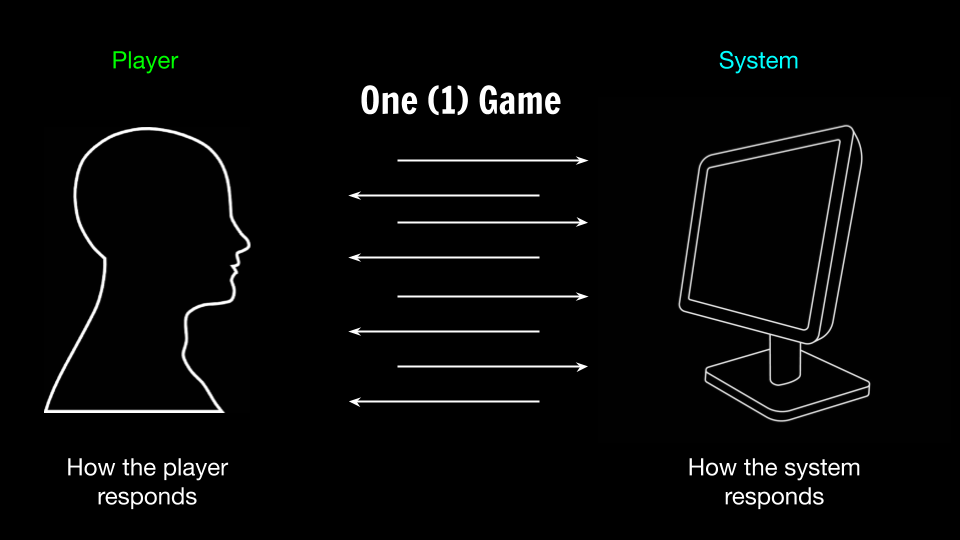

I would also say that games and digital narrative are just a sequence of actions. Sometimes they’re laid out very clearly, like here in Zork where you can see every component action that makes the story. But in a more general sense, any digital narrative takes what on stage would be a conversation between two people and just replaces one of them with a computer.

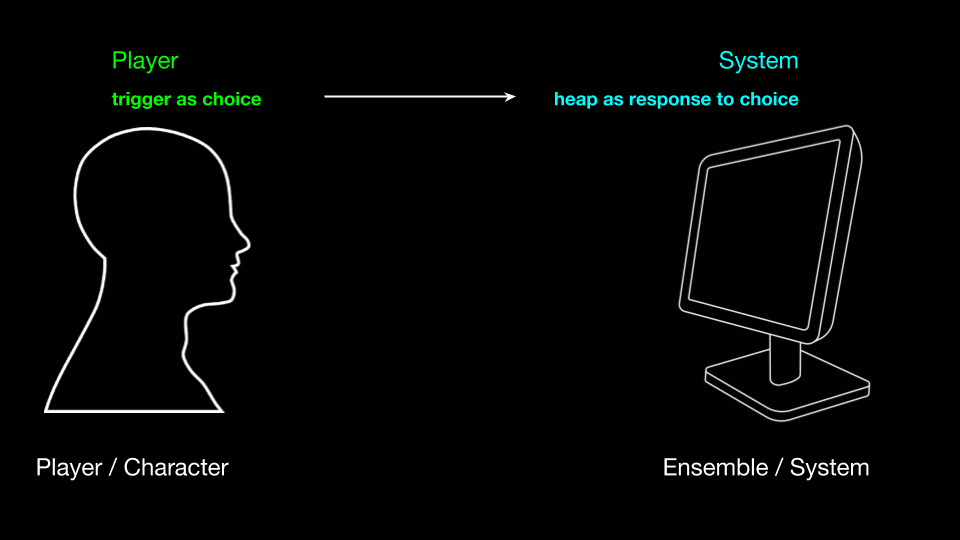

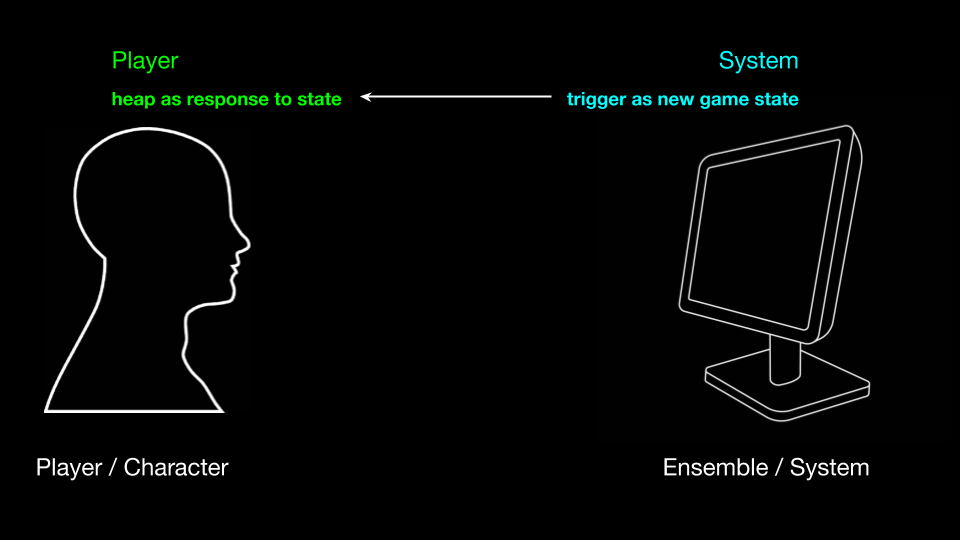

The relationship of trigger-heap becomes two separate acts: there’s the player who does the trigger of taking an action, then the system responds with a heap.

That heap prompts the player to respond, back and forth. At the end, a game is also a series of actions, of triggers and heaps, between the player and system.

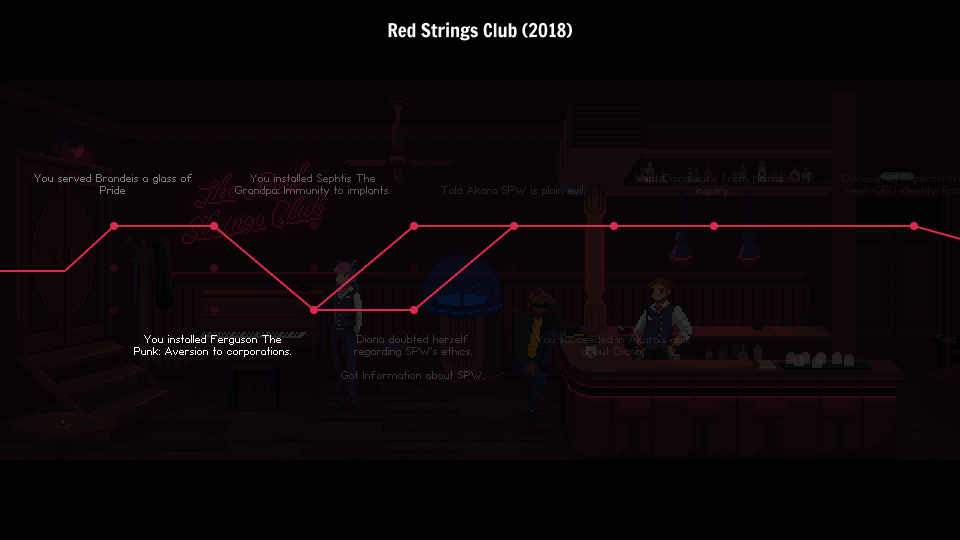

I recently played Red Strings Club, which does an interesting visualization of this. You can actually see a screen that charts out from the beginning of the game to the end, and at each point, there’s an illustration of the choices you made as a player (triggers), and how the story responded (heaps).

It gives the player the idea that had they chosen different triggers, the story would have responded with a different heap.

Which means that in a general sense, we can consider a sequence of actions not as just a play or a game, but as the general structure of a narrative.

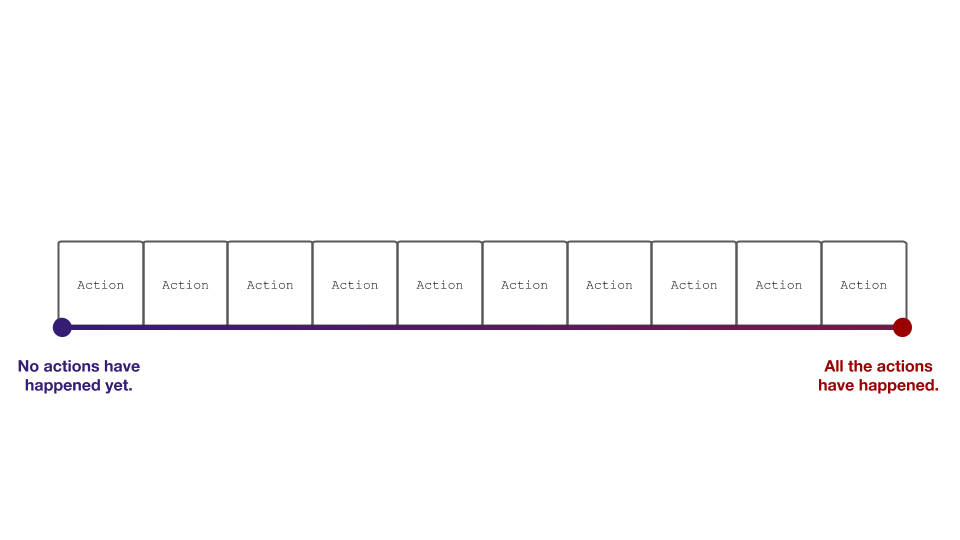

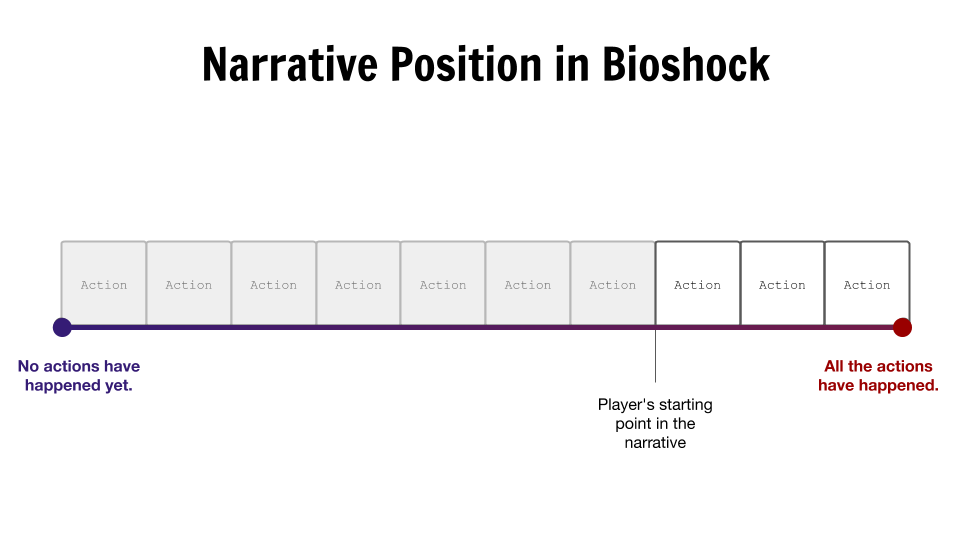

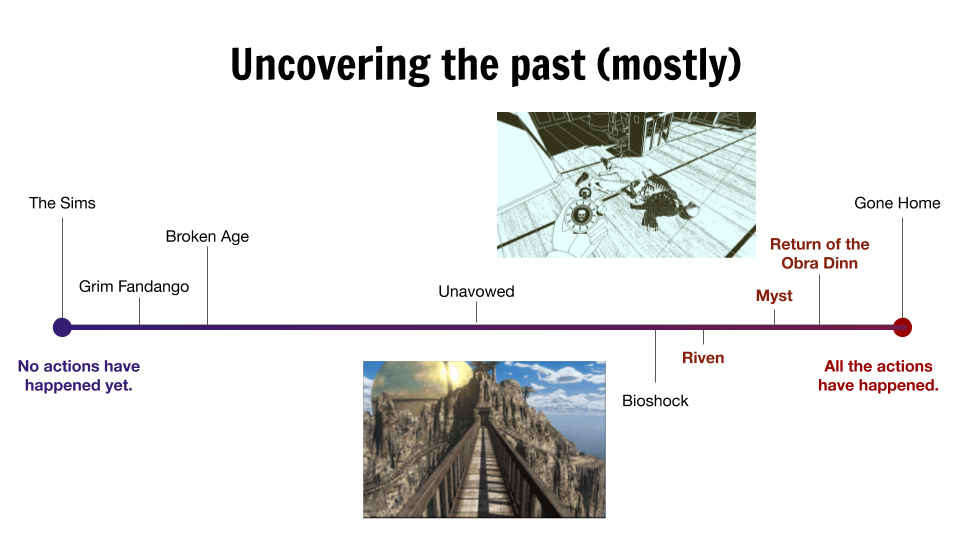

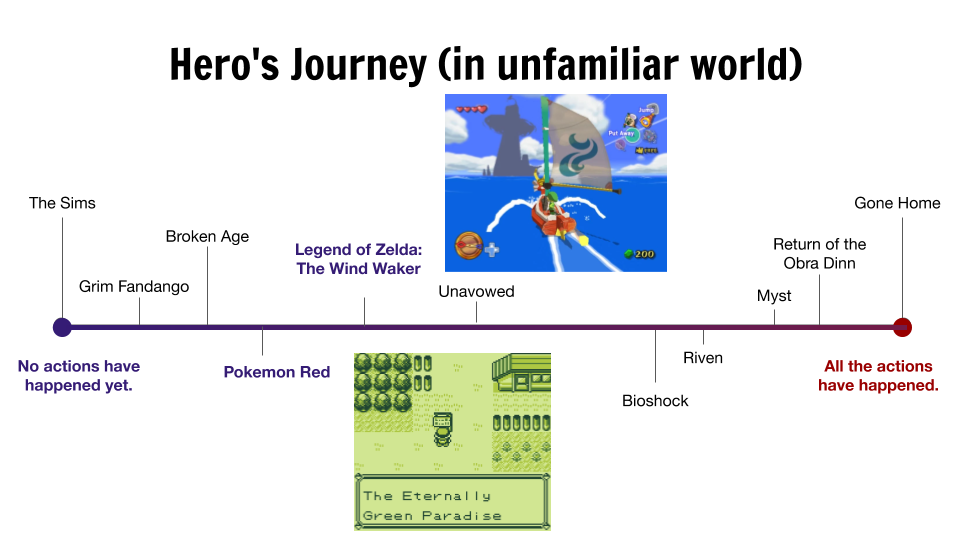

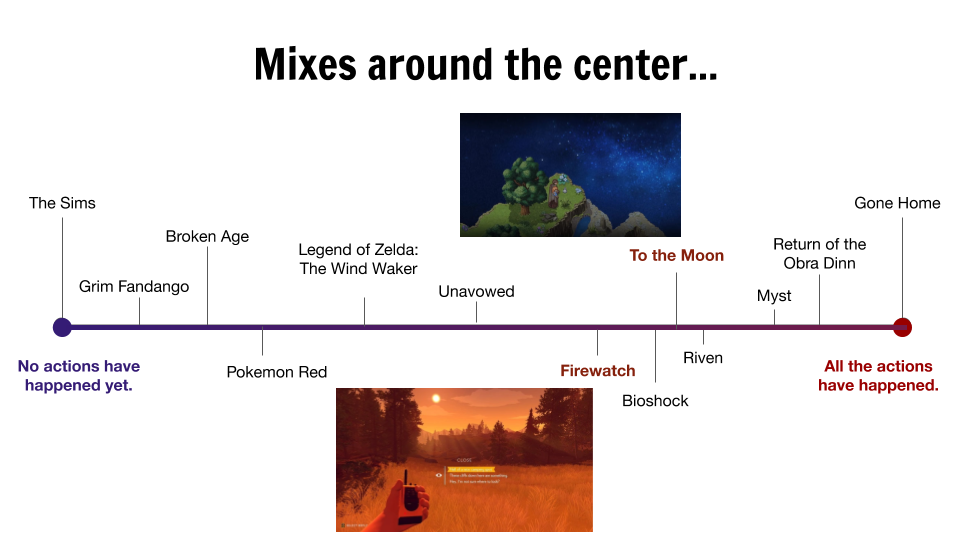

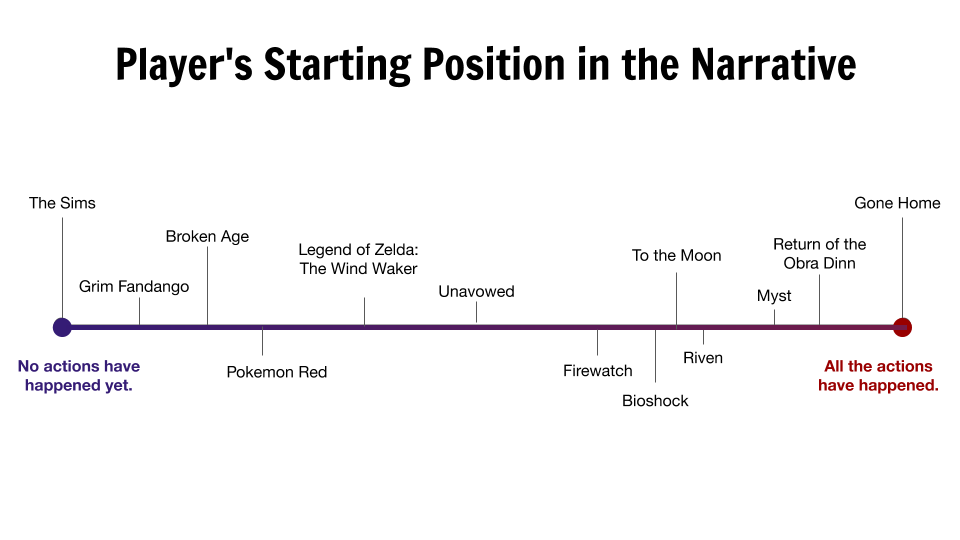

If you have this sequence of actions, you can think of it kind of like a line where at the beginning of the narrative, no actions have happened. At the end of the narrative, all the actions have happened.

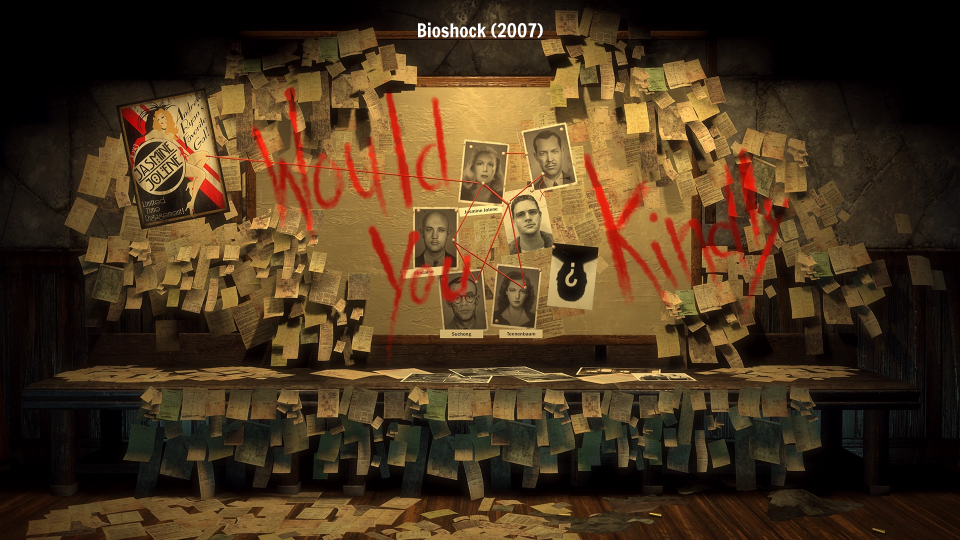

Consider a game like Bioshock. It’s a game that contains a deep, rich narrative, but a lot of what’s compelling about the story isn’t the actions the player takes during the game. A lot of it is about actions that happened before you as a player entered the game. Things like history discovered as audio logs, seen in the environment, or recounted by other characters. When a player starts Bioshock, the majority of the actions that make up the story have already happened. You as the player are just taking the final steps to complete the narrative.

If we plotted it on this line, we’d see the player starting fairly far along in the sequence of actions of the narrative. You could ask a similar question for any type of narrative game: where along the sequence of the narrative does the player begin taking their own actions?

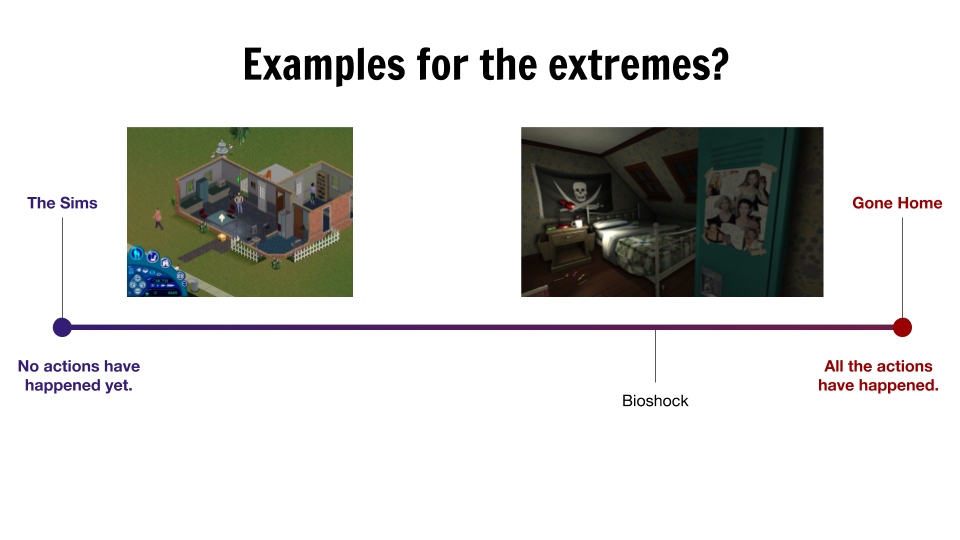

(A brief disclaimer: there are two poles on this line, neither of which intended to mean “right” or “wrong” designs. This is also going to be really subjective, based on my opinion, so feel free to argue with me afterwards)

Any time I want to plot examples on any graph, I like to label the poles. So first, are there any games where literally no actions have happened before you as a player start? The only thing I could think of in that pure camp is a game like The Sims. The characters in The Sims have lives that literally begin when you as a player begin, and end when you decide to remove the ladder from their pool.

Then all the way on the extreme, I’d put Gone Home, a game where the entire game is about uncovering actions that have already happened. You’re not taking actions that move the narrative forward, you’re discovering a narrative that already in the past.

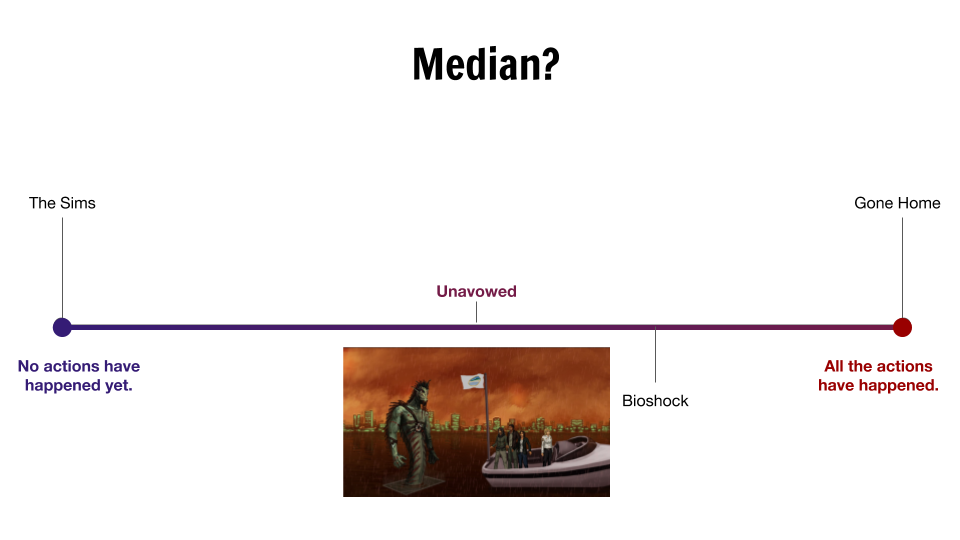

What would fall directly in the middle, where almost half the narrative has already happened before you start as a player, and another half happen after the game begins? Unavowed by Wadjeteye Games came to mind. The player character start the game having forgotten the past year of their life, and about half the game is about understanding what happened during that year. The other half is about fixing the mistakes that you made during that year. Maybe not exactly 50/50, but a mix of understanding past actions and creating new actions to move the narrative forward.

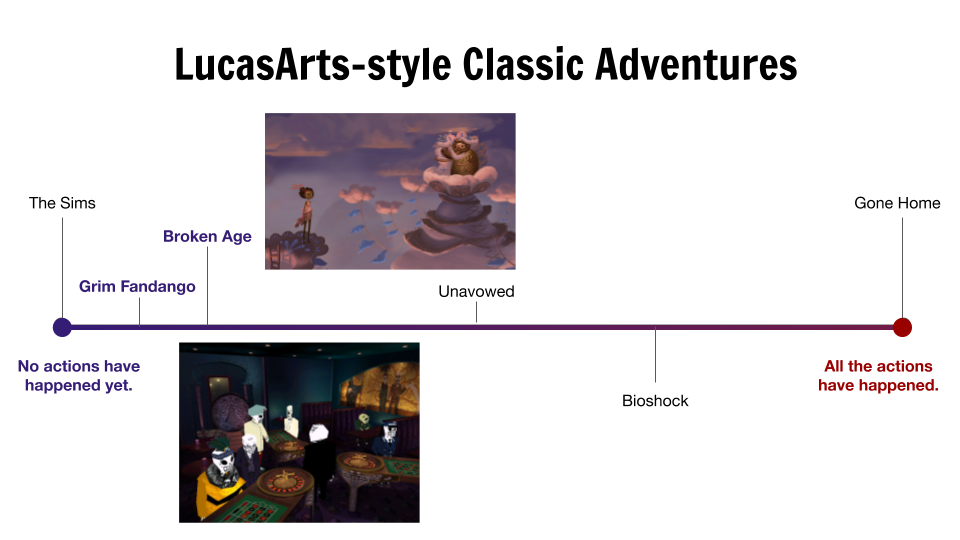

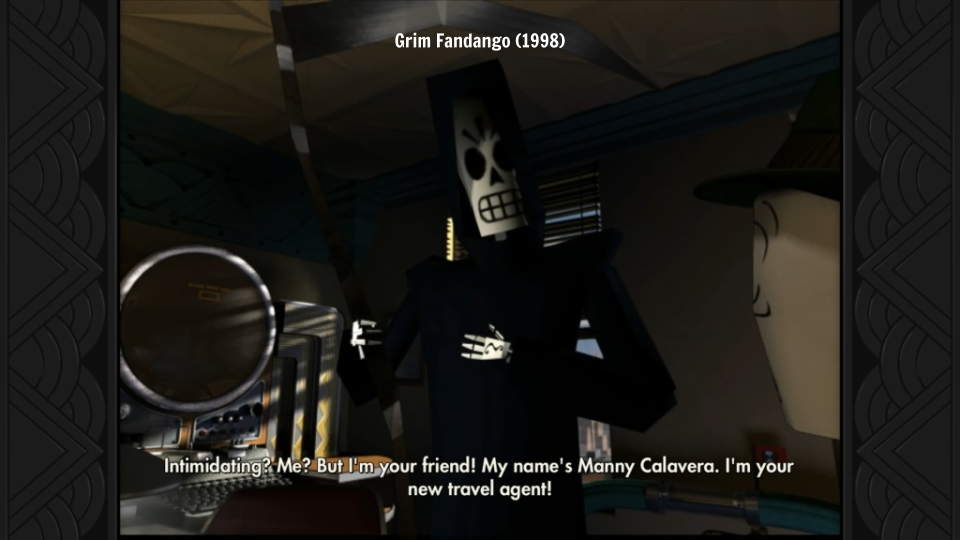

Some games that aren’t quite pure “no actions have happened yet” but are still fairly far along are some of Tim Schafer’s adventure games. The stories of Grim Fandango or Broken Age follow a Hero’s Journey structure fairly closely, with a small part of the game about understanding the past of your character, but the majority is spent creating new actions.

In many exploration games, nearly all of the game is about uncovering things that have already happened. In games like Myst and Riven, you take a handful of actions that move a narrative to its conclusion, but mostly just explore and discover stories from the past. Return of the Obra Dinn does an interesting spin on this genre: the actual gameplay acknowledges a series of actions has already happened, and presents a very formalized way to document what each of those actions were.

As we move closer towards the middle, I view action-adventure RPG games a little more to the left side. Mostly driven by your character’s journey, but also a fair amount of learning about the world and ongoing stories. There’s all kinds of other things that fall in the interesting middle. To the Moon is both uncovering the past but taking significant actions in the present.

Firewatch pulls multiple narrative threads together, some of which involve learning about the past lives of characters, while others develop new relationships in the present. It also does some interesting subversions of this duality, placing some actions that actually happened in the past appear like they’re happening in the present, and vice versa.

Again, none of these approaches are right or wrong, but there’s two interesting takeaways for me:

- When analyzing or playing games, it’s an interesting way to understand how a game is telling its story. How much is it being created by the player, and how much is being discovered?

- For anyone who makes games, it’s an interesting lens to understand where your story falls, and whether there’s anything interesting to be done by nudging it farther along either end of this spectrum.

For instance, the game Lamplight City by Grundislav Games plays with this concept in the detective genre. A detective game by design tends to involve mainly uncovering events that happened in the past (the job of a detective is to detect, after all). However, it also adds narrative threads with characters building relationships in the present on a parallel narrative track. It’s an interesting way to mix it up and create a richer weave of narrative.

Curtain falls on Act I. This is typically where the intermission would be, but we don’t have time so instead, the curtain rises on…

Act II

After the first act, you might be thinking: Hey Aaron, that’s great and all, a play being comprised entirely of actions. Sounds reasonable. But I’m calling you out! What about things like complex characters? What about deep internal struggles and thoughts? What about challenging moral arguments? These are all part of narrative too, right?

I would say: No!

Or at least when you write for the stage, you do not write those things. You cannot write them! The only thing that can get written is action. The only thoughts that a playwright can create are the thoughts implied by a character’s actions. The only characterizations they can make are the character interpreted from actions. The only moral arguments we can make is the moral argument proven by actions.

Here’s a quick thought experiment: who has ever seen a movie, read a book, or played a game that has a moment where a character has an idea, out of the blue, that solves whatever problem they had? How many people felt like that was cheap and not fair? It’s because that’s a thought that didn’t arise out of an action. If there had been some trigger that caused the thought, it would have felt way more legitimate since it was connected to action.

Who has ever experienced a narrative where a character was supposedly the good guy, but did terrible terrible things that were never questioned? Maybe a game where a hero slaughtered thousands of people, and this is never examined in an interesting way? That would be a case of the character’s actions dictating who they are more than who the writers intended them be.

For moral argument, the actions that are taken during a narrative expose the rules of the universe. This is a vision of a moral system that the author wants to put forth. It implicitly shows the way a person should behave (we’ll look at this more in Act III, so right now I want to focus on the character aspect).

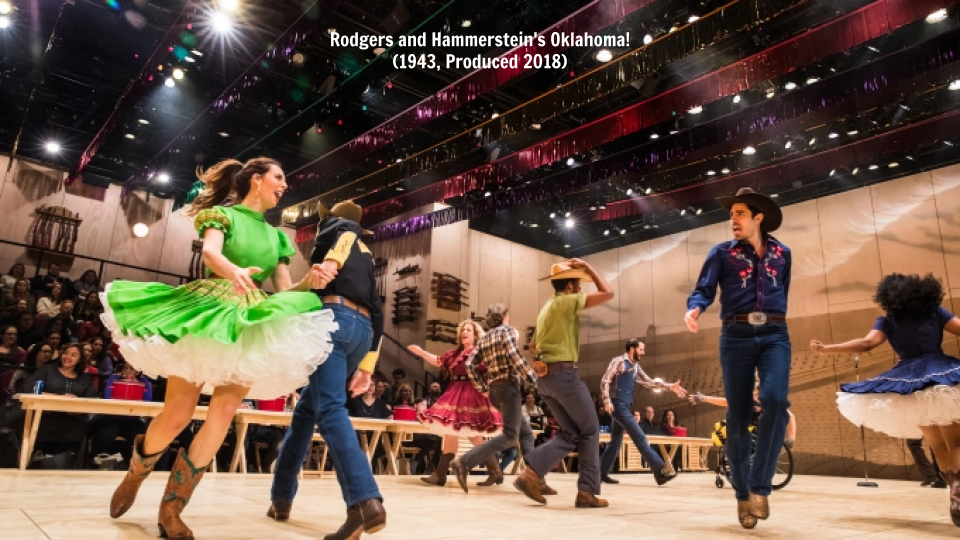

A really interesting example of this concept is the current production of Oklahoma! on Broadway, touring the country later this year if you don’t live in New York. It’s directed as Daniel Fish, who’s mainly known as an experimental theater director. He takes this show from the 1940s and stages it without changing a single line, or changing a single action from the narrative, and yet updates it to suddenly feel very dark and menacing. It’s challenging and incredibly relevant to today. How does someone take a script and without making changes, provide a reinterpretation?

The actions themselves don’t need to change, but the context has changed. Characterization and theme are based on the audience’s interpretation of the actions. Using a director’s toolbox and modern sensibilities, actions like shunning someone from society can be viewed as either based on good intentions or malice. An audience viewing the same actions with the new context can generate different understanding of who these characters are, why they do what they do, and ultimately update their interpretation of the show’s themes. Since it’s only the actions that are written, these intangibles are formed by the viewers, under the guidance of the director.

A lesser-known theater piece is my one-man play, The End of Commercials. It was inspired by a Sizzler commercial from 1995, for which I had written a 45-minute deep reading. After I’d written and started rehearsing the show, I realized that just by speaking the lines (which is taking an action), the person presenting the argument actually wasn’t me. I’d accidentally created a character, their main characterization being an unhealthy obsession with Sizzler. It’s bi-directional: anyone taking actions is a character. Any action taken has an implied thought behind them. It enabled me to rewrite the show, making it richer and deeper, by realizing there was a character at the center, not just me.

Another interesting lens on this is the much lauded improv duo of TJ Jagodowski and Dave Pasquesi, TJ & Dave. Their performances are mind-blowing: it’s a 1-hour show, where they don’t take a suggestion. They start by looking each other in the eyes for a full minute, without saying anything.

In beginner improv classes, you’re taught the importance of understanding who you are in a scene right away, and what your relationship is to the other characters on stage. But experienced improvisers know that a character isn’t a label like “father,” “son,” “mechanic,” or “teacher.” A character is the actions that you take towards other people. The reason TJ & Dave stare at each other is to understand how they feel about the other person, on two aspects:

- The heat (nice or nasty?)

- The weight (big or small?)

Just by understanding those two feelings, they know what actions they will take to try to affect the other character. Then, by taking those actions, their full characters emerge. They end up close enough to each other that they then have enough fuel to go off of for the entire hour.

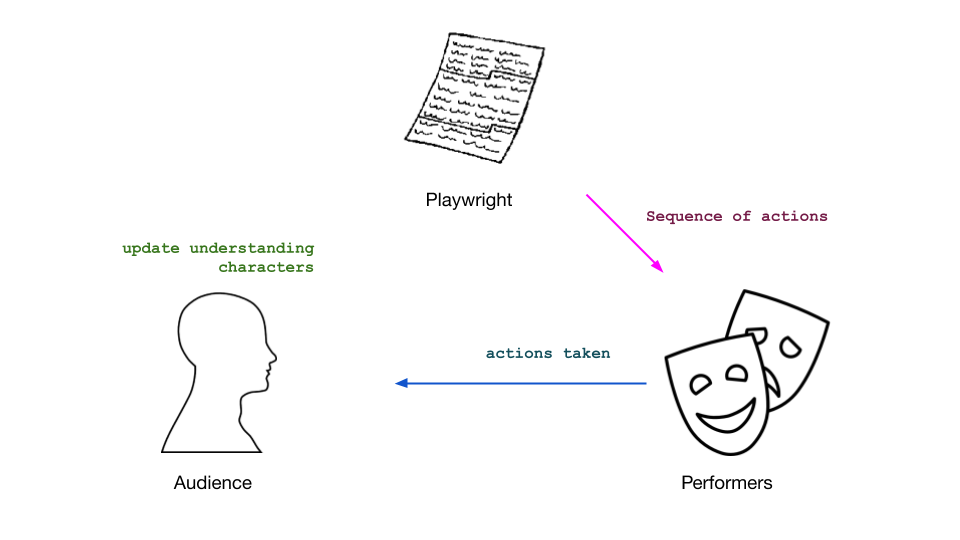

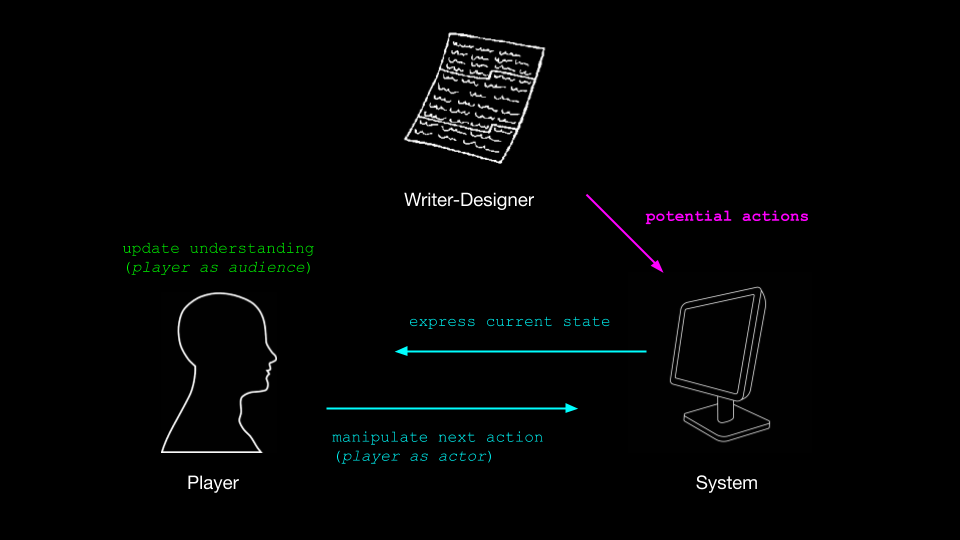

Playwrights describe a sequence of actions, which the performers then present to the audience, who see the actions. The audience forms a picture in their heads of who the characters are, what they’re thinking, and what argument the playwright is putting forth.

In digital narrative, there are a set of potential actions that are given to a system. That system presents the game state and the potential actions to the player, and the same interpretation happens in the player’s head.

But there’s an extra step, where they player gets to manipulate what the next action is going to be. It creates an interesting duality for the players: they’re acting as both an audience member and an actor in the narrative.

It raises an interesting challenge: a character is the sum of the actions they take, and a character’s thoughts are someone’s interpretation of why the actions were taken. But for played characters, the character isn’t the one taking the actions, the player is. And the character isn’t doing the thinking, the player is.

The first question is: how closely aligned are the player and the character? Are they exactly the same, or separate? A game like Myst has a separation that is essentially zero. The character in Myst is someone who’s been transported to a strange island with no context, confused, and no idea what to do next. The player, meanwhile, is someone who’s been transported to a strange island with no context, confused, and no idea what to do. The player and the character are in the same mental state, they have the same information, and their goals are the same.

Zork: Grand Inquisitor refers to this as the “ageless, faceless, gender-neutral, culturally-ambiguous, adventure person.” The strategy is to make a character that’s empty, so the player can completely inhabit them.

A game like Grim Fandango takes the opposite approach. The player inhabits the character of Manny Calavera, a wise-cracking, self-serving, down-on-his-luck travel agent in the world of the dead. A player might not be any of those things (although chances are, they relate to some of them). However, the goals of the player, like exploring the world, solving the mystery, escaping the dangers, and saving the girl, are the same things that Manny needs for both his conscious goals and his unconscious character development. We not only want to see Manny succeed, we want to see him go from self-serving to altruistic. Fortunately, the actions the player completes force Manny to do just that. The player’s goals are aligned with the things the character should do to complete both his internal and external journey.

Back to Bioshock. Its famous twist calls out the reality that the player is choosing responses (triggers based on heaps), and the character simply follows that choice. The fiction of most games is that the player choosing is the equivalent of the character choosing. Bioshock‘s confrontational assertion is that while the action of the player and character are identical, they’re identically following, not identically choosing.

A second interesting question: if characters are the sum of their actions, how do you create meaningful characters, but still allow the player to take meaningful actions? By our definition, taking different actions should lead to a different character.

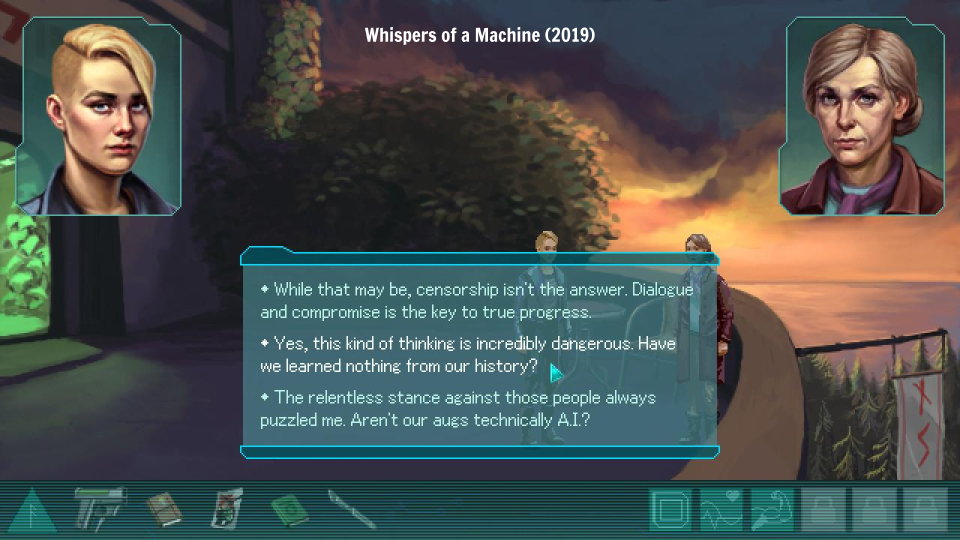

Whispers of a Machine essentially creates three separate characters that the player can “become.” Actions are divided into empathetic, assertive, and analytical. Based on the choices a player takes, there’s three variations for the protagonist’s character to grow into. This branching strategy works when you have a limited set of possibilities, but what happens if you want a character to expand beyond a static set of options?

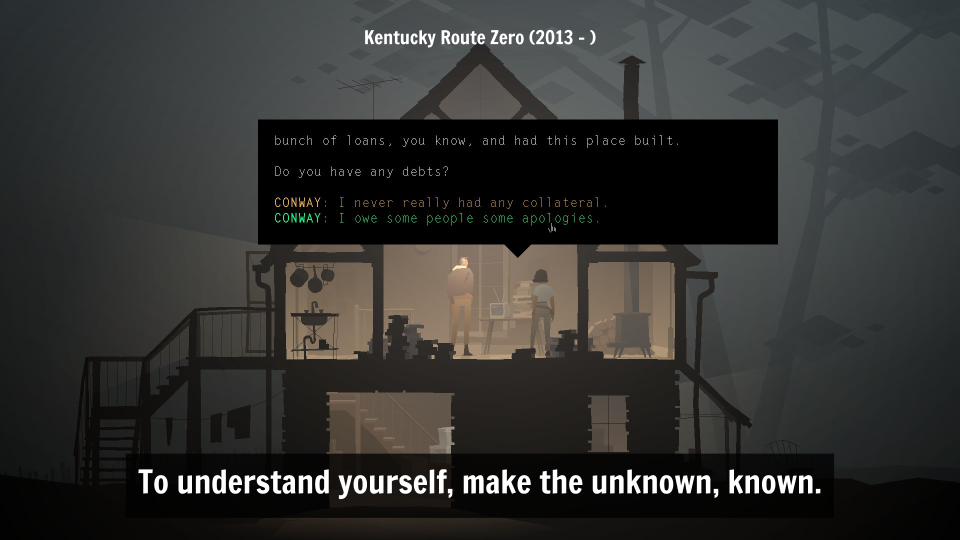

In the game Kentucky Route Zero, this is handled rather elegantly. Few, if any, of the choices you make affect the plot in meaningful ways in terms of the direction the story takes. Instead, the choices between different options further define the characters. It would seem like this would make it even more challenging to keep characters consistent, but KR0 resolves this by not making choices reflect surface personality (e.g. I’m happy vs. sad, high energy vs. low energy). Instead, options are reflections of a character’s deeper self, like values and identity, the complex systems everyone contains.

I find this impactful because human nature is to have consistent external identity, but everyone has a complex internal identity. Beliefs stand in contradiction and we live as paradoxes. That doesn’t need to be resolved if the options are beyond surface level. Instead, it leads to richer characters.

This same question is dealt with subversively in The Stanley Parable. The game’s narrator tells the character what action they are expected to take, although as a player, you can choose something different. If the player doesn’t follow the character’s supposedly “correct” path, the narrator will even adjust to make it seem like the player’s choices were the character’s predetermined path all along. If you go too far off the path however, the narrator starts to berate you (the player) for exploiting the difference between what the character is supposed to do, versus what the player wants to do.

So to summarize, this duality leads to three interesting questions:

- How close is the player as an audience to the character as an actor?

- How are the player and character motivations aligned (or subverted)?

- Are the choices the player makes contributing to a unique understanding of who the character is?

Act III

I want to return to the idea of a narrative as a series of actions. A wrinkle I’d like to add is that a narrative is not a sequence of just any actions.

To illustrate, look at Smokers Allowed, a site-specific theater piece created for the comedy-reality series Nathan For You. The host was trying to get around an indoor smoking ban for Los Angeles bars, and noticed there’s an exception where smoking could be done indoors for theater productions. So he made an entire bar a site-specific production called Smokers Allowed, and anyone who entered the bar was a part of the production, therefore allowed to smoke.

Of course, when he brought an audience in to watch the “play,” the host discovers that people going about their actions on a typical night in a bar does not lead to particularly compelling narrative.

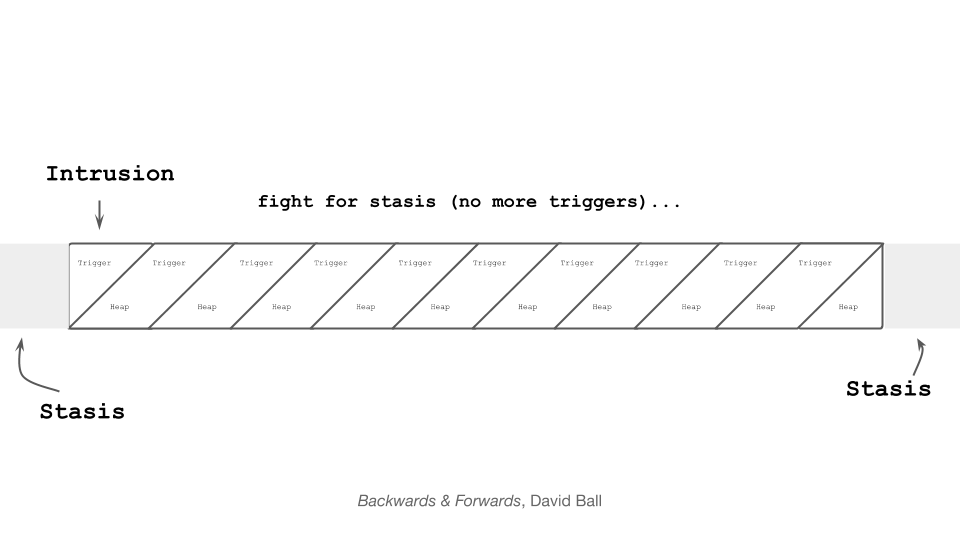

There’s actually a structure in theater that shows how certain actions lead to a compelling piece. A narrative begins with stasis: a state where things might be going on, but they’re not actions. There aren’t consequences. For instance, Romeo & Juliet begins with the Montagues and Capulets in conflict with each other. It’s not a happy stasis, but the tension could go on that way forever. Nothing is changing, or forcing it to change.

But then, something happens. The intrusion. It’s the first trigger of the play. After this, the stasis can no longer hold. This is when Romeo first sees Juliet, and decides to court her. Suddenly, the family’s feud can no longer co-exist with the emerging love.

After that first trigger, the entire play becomes a series of triggers and heaps, with characters trying to establish a stasis again. They want a place where they no longer need to fight to be comfortable. For Romeo & Juliet, that would mean the ability to stay together as a couple.

The characters keep fighting until they get to the final heap, the action after which there are no more consequences, establishing a new stasis. If you’ve ever heard of a narrative described as a character following a want, their journey will either end with receiving that want, or not, which becomes a stasis state. When Romeo and Juliet both die, the families come together with the hope that their tension might be resolved.

Here’s an image of Romeo & Juliet, a play from 1597:

Why is this structure effective? It’s all about what goes on in the audience’s head.

At the beginning of the show, like Jack Viertel says, the audience is in trouble. They’re fearful because there’s infinite potential for what might occur before them. That uncertainty makes people feel uneasy with anticipation.

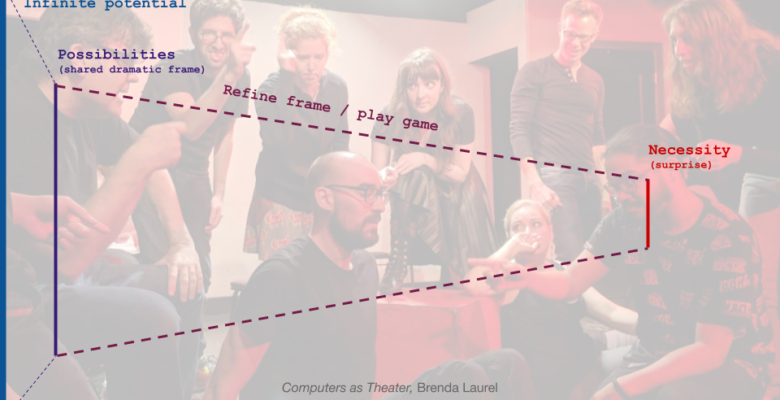

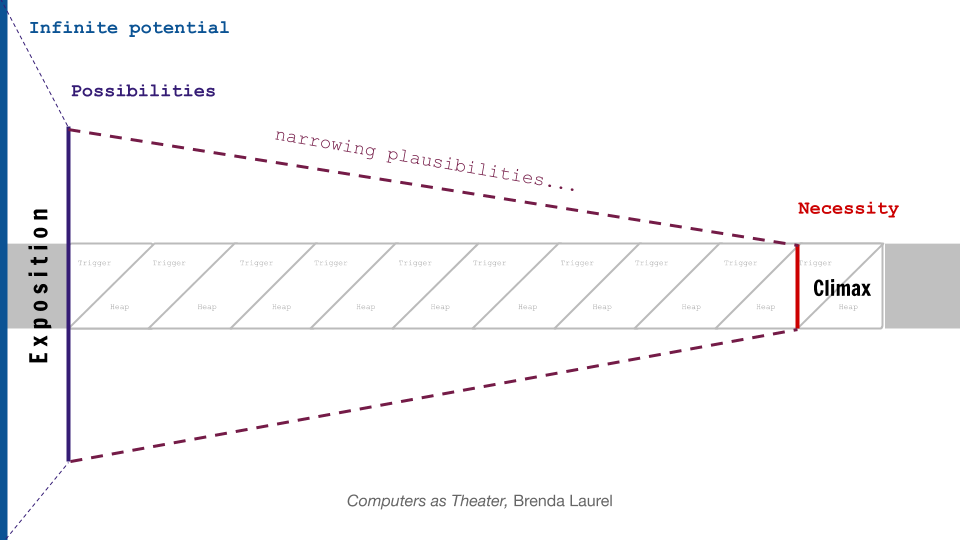

But over the beginning of a play, that infinite potential is reduced to a set of possibilities. This is the exposition, the understanding of the universe and what is happening in it. The audience now understands the set of actions they can reasonably assume might happen onstage, and they start to relax a little.

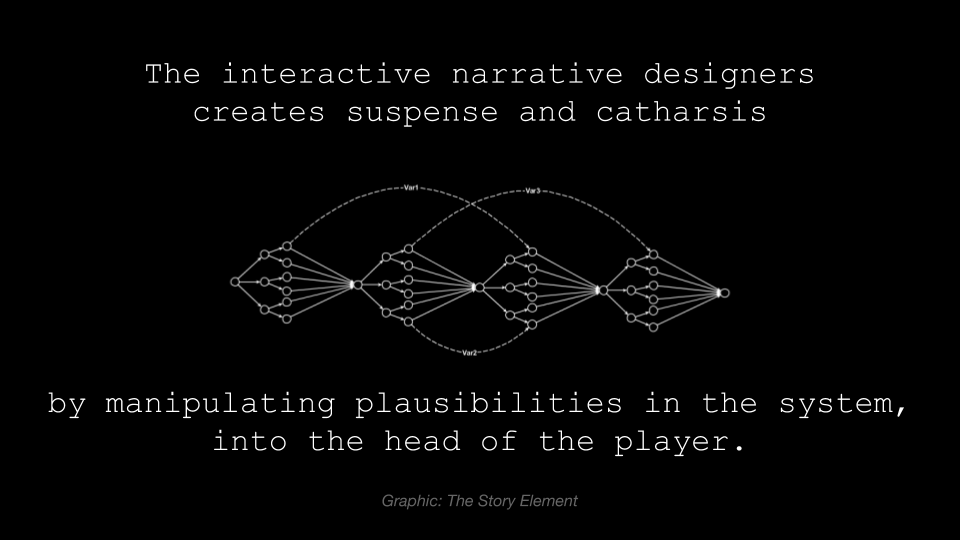

From that set of possibilities, they audience meets the characters and sees the actions they take. They start to understand what’s going on in the characters’ minds. They can start to predict what actions those characters might take in the future based on what they’ve done in the past. The possibilities gets reduced to plausibilities, what actions are likely to happen based on what the audience knows. In a good play, the audience can typically imagine a few plausible actions that could lead to wildly different outcomes for the characters, which creates suspense in their minds as they wonder which will actually happen.

Eventually, the show reaches a point of necessity. The final action of the play is taken, and the set of plausible actions that might happen are reduced to a single action that does happen. This is otherwise known as the climax, and after imagining possible futures in their heads, the audience receives catharsis at knowing the reality.

The reduction of an infinite potential for actions, to the possibilities of the universe, plausibilities for the characters, and necessity of the ultimate action is what makes that structure so compelling. It creates an ongoing flow of suspense and catharsis that keeps the audience hooked.

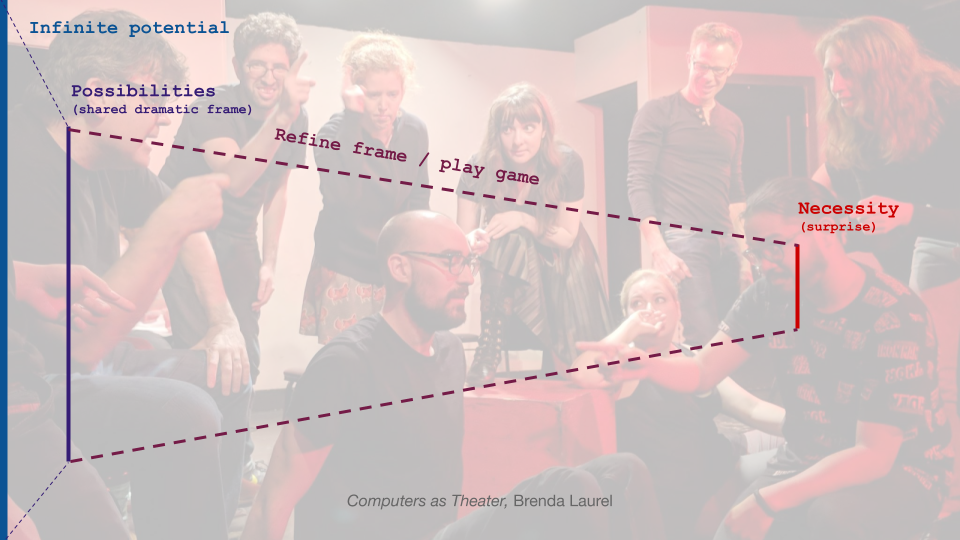

There’s an interesting use of this structure in improv, too. This is a photo of my improv group, Darkness Falls. People sometimes come up to me after a show and ask cheekily, “That was great, but how much of that did you all plan out beforehand?” Of course, we never plan beforehand, and part of what we love about our own particular blend of improv is the risk that something might go horribly wrong. However, when things go right, people are sometimes skeptical that we could have pulled something off without preparing in some way beforehand.

But there actually is a secret sauce to improvising onstage with a group. Feel free to take it out of this room and share it with others, there is no magician’s code for improv.

At its core, improv is simply taking the structure I just discussed and collectively exploiting it while in-flight. At the beginning of a scene, anything has the potential to happen. But as soon as a single line is spoken, it communicates a set of possible actions that can happen next (and equally as important, what cannot happen next). In the academic literature on improv comedy, this is referred to as a “shared dramatic frame.” The group develops a shared definition of what actions are possible, and exploits it together.

For instance, we had a show a few weeks ago where someone started a scene by saying “Thank you all so much for coming to Linda and my wedding.” It immediately communicates what actions could happen next. It’s still an infinite set of possibilities! The next action could be an argument with the bride, an interruption from the father-in-law, or getting distracted by the dessert. But now that next action has narrowed to a specific boundary of actions that happen at a wedding reception. Each line that gets said communicates more information, and narrowing that frame even more.

For improv, going from the infinite potential of a new scene to a shared dramatic frame creates that same sense of suspense and catharsis. It’s a matter of losing and regaining control for the improvisers. In a play, whcih is always under complete control, the writer manipulates probabilities in the head of the audience to parallel that sense of wildness, by changing the likelihoods that a particular action will happen.

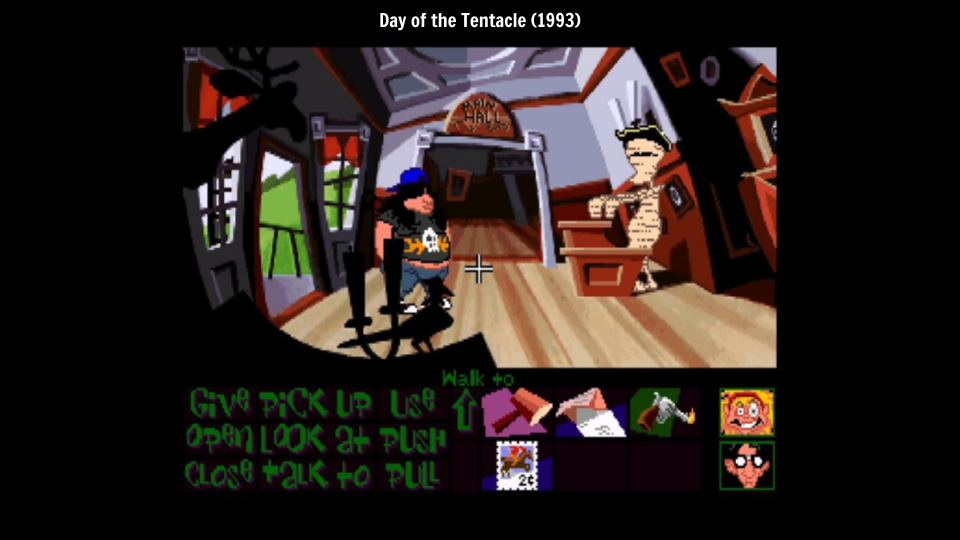

A digital narrative designer is very directly controlling similar possibilities of available actions, too. In a game like Day of the Tentacle, all of the potential verbs are laid out (examine, pick up, use, etc.). The players have a very clear idea of what actions are available in the future.

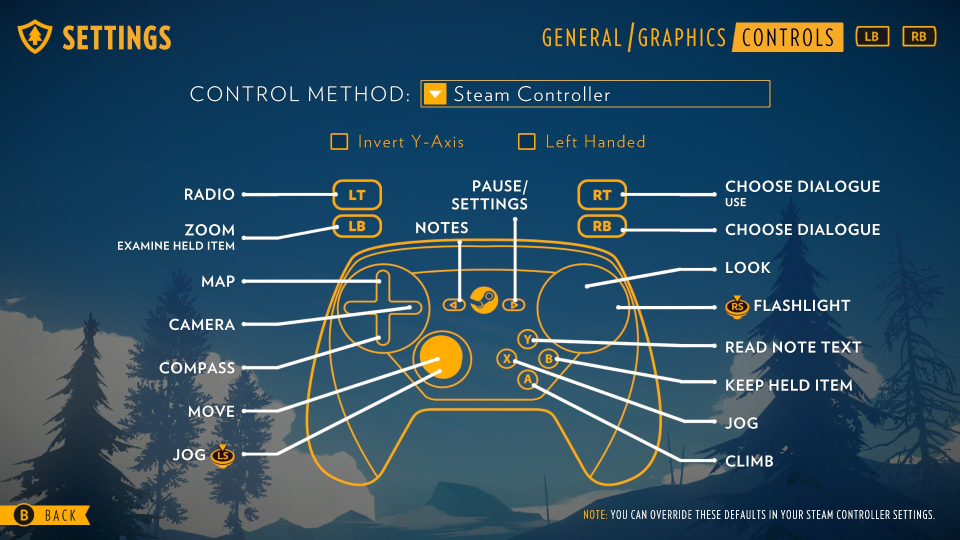

In a more contemporary game like Firewatch, even though it feels like there’s an infinite number of micro-choices players can make over where to walk or look, behind it there’s still a closed set of actions constrained by the controls that are enabled. Firewatch also subverts the idea of probable actions, by contrasting the types of actions that are plausible in the world of a game (such as secret agents and mind control) and the actions that are plausible in the real world.

There’s an extra step of indirection in digital narrative, because it’s a system not a script. The game designer is creating suspense and catharsis through the system that’s designed, and the player understand the possible actions via that system. The player learns the system as they explore the world, and this creates the possibilities and plausibilities in their head.

Which returns to the idea of a moral argument. There’s lots of possibilities for what could happen next in a story based on what’s possible, but at every point only one action actually occurs. Story-based narratives are the story of characters who make choices, who could have chosen differently, and what happens as a result.

Based on the choices a character makes, either good things or bad things will happen (or, they won’t happen). The possible actions, the choices the characters do make, and the consequences together form a moral argument: rules of the author’s universe. Rewards and punishments present an argument about the choices a character (or, human being) should make, given the options available.

Which means I get to talk about my favorite thing: Ludonarrative Dissonance!

[NB: a mix of audible groans and cheers from the crowd, followed by the Space Jam theme song]

If you’re not familiar, Ludonarrative Dissonance is a term invented by Clint Hocking to describe the situation where a game’s narrative tries to send one message, but the narrative sends another. A common example is, again, Bioshock, which has been accused of promoting altruism with its narrative, while promoting selfishness in the gameplay.

Since this has been a hot topic for a while, I’m going to sidestep by claiming: it’s actually easy to read the moral argument a game is making, by focusing on the sum of how actions are rewarded and punished (for both the character and the player). What types of heaps are given for the various triggers a player might make?

Again to break it down: moral argument is the sum of the action, which get rewarded, and which get punished. And since every game contains actions, rewards, and punishments, that means every narrative game is necessarily making a moral argument. Some actions will be rewarded or punished (or not rewarded/punished! It has to fall in one of those categories!), so it’s impossible to create a narrative game without a moral argument embedded within it.

For any game creators in the audience, it’s important to be conscious that any narrative system you design will contain a statement of morals. Be sure to think about the message this is sending, and whether you intended to send it or not.

I claim it’s easy to understand the moral argument of a game narrative by looking at the actions, and considering what was rewarded, and what was punished. To test this, I took some of my favorite games discussed in the talk and tried to do a moral reading:

I started with Myst, which is probably the first adventure game I played. In Myst, in order to advance and complete the story, you have to explore, be curious, and turn over every rock. But also, if you are too curious, and you don’t consider the advice people have given you, it can cause you to trap yourself and lose. That sends a message that curiosity is a virtue, as long as it’s coupled with a sense of healthy restraint.

In Firewatch, in order to advance and get past narrative obstacles, you need to relay messages back and forth with someone else. Throughout the narrative, the choices that get characters in trouble are when they make unilateral decisions, or abandon others. That adds up to the idea that life is meant to be lived with a partner–it’s not a solo experience.

And lastly Kentucky Route Zero, which is kind of challenging. It has a magical realism narrative, and doesn’t have many “wrong” choices you can make. But in order to advance and complete the game, you need to typically talk to everyone around, and hear what they’re saying. You bring others into your party to join the narrative. With a protagonist struggling with his identity at the end of life, it says to me that in order to understand yourself, you need to take the unknown places and unknown people, and make them known.

I’m sure that the “games as art” debate, for people in this room, is probably already settled, but these to me are very clear and compelling narrative themes. I find them very touching, and it’s one of the reasons I find interactive narratives so compelling in the first place. The ability to not just read that deep meaning, but to experience it, I see as a great gift.

Further reading

- Backwards & Forwards, David Ball (1983).

- Computers as Theater, Brenda Laurel (1991).

- Group creativity: musical performance and collaboration, R. Keith Sawyer (2006).

- Improvisation at the Speed of Life. T.J. Jagodowski and David Pasquesi (2015).

- The Secret Life of the American Musical, Jack Viertel (2016)

- Poetics, Aristotle. (c 335).